Outside Listening: Mapping Soundscapes

Author: Cynthia Nicol

In May the hummingbirds arrive on Haida Gwaii. One afternoon my good friend and I sat out on her deck and were entertained for hours by the hummingbirds. We counted 17 hummingbirds sipping the nectar from two feeders stationed on the deck corners. Listen … can you hear their calls? Can you hear the beating/buzzing sounds of their wings?

Soundscapes, like landscapes, tell us a story about the place. Soundscape ecologists like Bernie Krause and Hildegard Westerkamp have recorded sounds in the natural environment for almost 50 years. Over time they have mapped how the sounds of the environment have changed. In some cases the hum or buzz of urban life on land, shipping traffic on sea, and air-traffic have transformed our soundscapes.

You can participate in being a soundscape ecologist by listening to and mapping the sounds outside in your backyard, or at a nearby park, or wherever you are.

Here’s one activity you can try by yourself or with others. You will need a piece of paper, pencil, and clipboard.

Now close your eyes and listen. Listen. Listen. Mark on your map what you hear.

- How far from you is the sound and from what direction?

- Maybe you hear the wind rustling in the trees, or a bee nearby, or the sound of bicycle, or the call of an eagle. Mark both the distance from you and the direction of your sounds.

- Try making soundscape maps at the same place over different days. What do you notice?

- Try making soundscape maps at the same place over different times of the day.

- What do you notice? What do you wonder?

Fractals in Plants 1

Author: Katherina von Bulow

I went outside fractal-hunting today. I was looking at plants, and here are a few of my findings: |

| A camelia flower, its petals going round and round. |

|

| Each branch of this shrub comes from another (thicker) branch and so on until the trunk. Below ground, its root system is like a branch system that we could draw as a fractal. |

|

| A red cedar branch. It’s Y’s all the way down! |

Fractals: What is the shape of a cloud?

Author: Katherina von Bulow

Cloud photos credit to: Susan Gerofsky

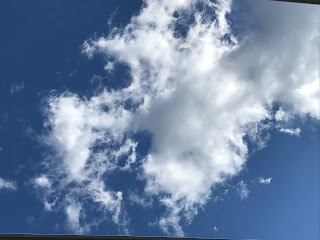

Here’s a lovely thing to do together, especially on a day when the sky is blue and those fluffy cumulus clouds are moving around in the wind. Try looking up (or better yet, lying on your back in the grass) and watching the clouds.

You might try photographing or drawing them, as I’ve done here. But how to draw a cloud? What shape is a cloud?

We have learned the names of shapes with straight-line edges like triangles, rectangles and octagons, and curved shapes with continuous line edges like circles, ellipses and parabolas. But none of these really describes the ragged-edged (and ever-changing) shapes of clouds.

We have learned the names of shapes with straight-line edges like triangles, rectangles and octagons, and curved shapes with continuous line edges like circles, ellipses and parabolas. But none of these really describes the ragged-edged (and ever-changing) shapes of clouds.

You might notice that some clouds look a lot like the maps of islands, continents and shorelines. (The bottom photo here reminds me of a map of Europe and the Mediterranean…)

Shorelines are also ragged-edged and changing, more slowly, because of forc es of erosion and tectonic shift. So if we can figure out what shape clouds are, we might also figure out what shape islands, continents and shorelines are!

es of erosion and tectonic shift. So if we can figure out what shape clouds are, we might also figure out what shape islands, continents and shorelines are!

Try looking at a small bit of a cloud you have photographed. Is there a small section of the cloud that looks almost like a miniature version of the whole cloud? If so, then you may have discovered a fractal ‘seed’ that can be copied bigger and bigger (and/or smaller and smaller…) to create the shape of the whole cloud!

That is what is meant by a fractal: a shape that repeats itself in more or less the same way on different scales ( really tiny, small, medium, large, really large…) to create a ragged-edged and evolving shape without straight-edged boundaries.

Here is a good explanation by a meteorologist at the University of Bonn, Germany about the ways that clouds are at least partly fractals (and not always completely so, as the big central parts of clouds are not as affected by wind turbulence as the edges).

Here is a good explanation by a meteorologist at the University of Bonn, Germany about the ways that clouds are at least partly fractals (and not always completely so, as the big central parts of clouds are not as affected by wind turbulence as the edges).

And here is a very nice film about natural fractals, featuring the mathematician who ‘discovered’ fractal geometry, the late Benoît Mandelbrot!

Try drawing the shape of bumpy or ragged edge of a cloud. It might be easiest to draw it fairly large on your page. Then, on each of the ‘bumps’ try drawing smaller bumps that have the same shape only smaller. Do that again, three or four times. Are you getting a shape that looks a bit like the edge of a cloud — or a shoreline?

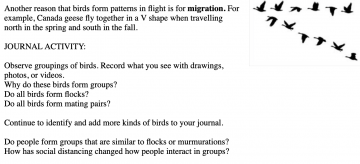

MATH IS FOR THE BIRDS! Part 2

This video is taken near Vancouver by Pacificnorthwestkate.

The flight velocity and direction of one bird affects 7 around it which multiplies throughout the group.Like the movement of schools of fish, murmuration is an example of scale free behaviour correlations. No matter how large the flock of birds is, the action of each bird will affect and will be affected by the action of all the other birds.This means that each bird’s range of perception is much larger than if they relied on direct interactions. Murmuration has been compared mathematically to magnets.